IMSI catchers, devices used to spoof cell towers and intercept communications, are one of the most resented open secrets of law enforcement. Strict non-disclosure agreements prevent them from being acknowledged as existing, let alone being used — but researchers think they’ve found a way to spot the shady signal-snatchers.

The devices, colloquially called Stingrays after a common model, work by sending out signals much like cell towers do; cell phones connect, identify themselves and send information like texts and calls through the fake tower, creating a sort of mobile wiretap. Critics have argued that innocent people’s data is caught up in this dragnet, but law enforcement has been less than forthcoming owing to gag orders from the companies that provide the devices.

What’s needed is an independent method of identifying IMSI catchers in the wild. That’s what University of Washington researchers Peter Ney and Ian Smith have attempted to create with SeaGlass.

“Up until now the use of IMSI-catchers around the world has been shrouded in mystery, and this lack of concrete information is a barrier to informed public discussion,” explained Ney in a UW news release. “Having additional, independent and credible sources of information on cell-site simulators is critical to understanding how — and how responsibly — they are being used.”

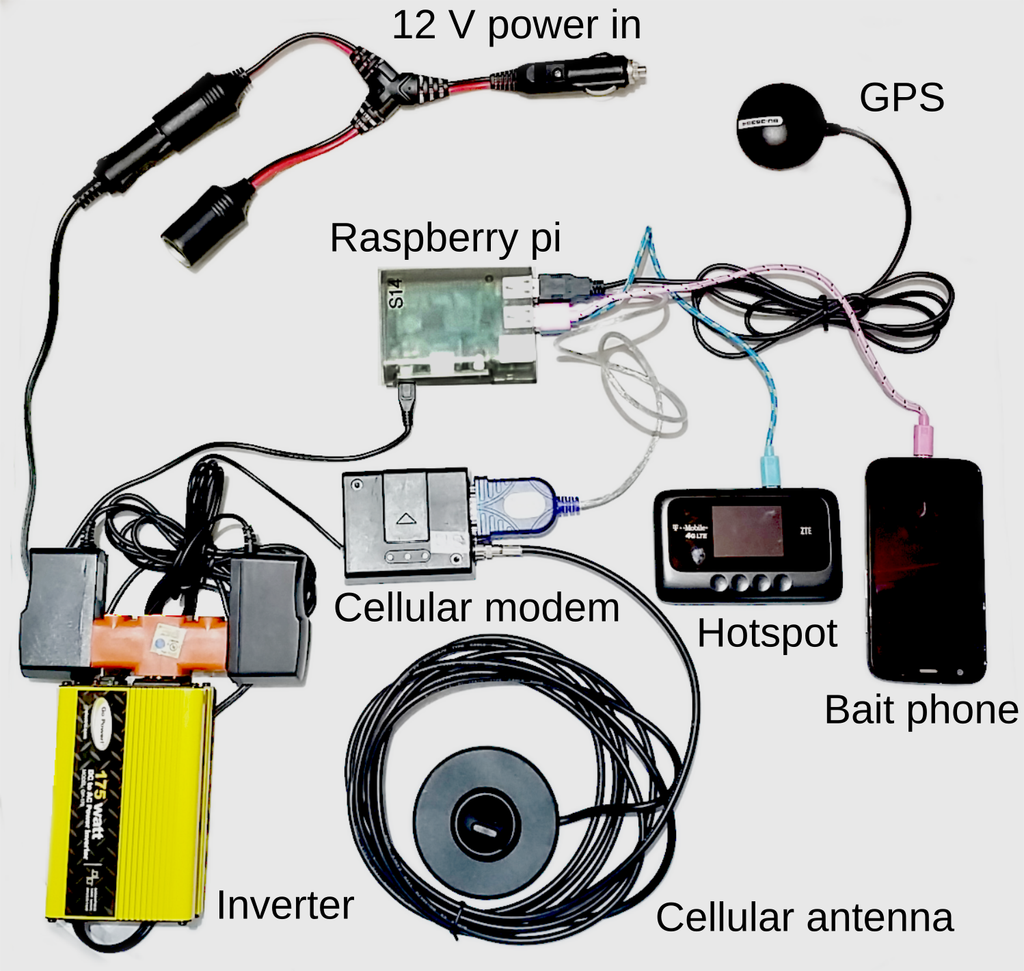

The team put together a sort of super-powered wardriving setup that uses a “bait phone,” GSM modem, GPS unit, Wi-Fi hotspot and other wireless doodads packed into a single box. These devices monitor and record the wireless signals they encounter. In order to cover as much area as possible, boxes were attached to 15 vehicles being used by rideshare drivers in Seattle and Milwaukee.

The baseline map shown as it grew; red signals are stronger and more reliable

Over a period of two months, the kits collected a baseline of wireless activity, including known towers, private signals and so on. But sifting through the data revealed some suspicious outlier signals.

One signal source, for instance, changed six times over the two months the frequencies on which it transmitted — unlike 96 percent of sources detected. Five of those frequencies were only able to be detected within 1,500 feet of the building.

One might write this off as a test or nanocell, except for the fact that this particular source happens to be located in or around an immigration services building run by Homeland Security. Could that be a Stingray, in position to target recent immigrants? The data is consistent with that hypothesis, but more data is needed to be sure.

The building in question, indicated by a diamond, produced many normal signals (green), but suspicious ones at close range (other colors)

“We want to be careful about our conclusions,” cautioned Smith. “We did find weird and interesting patterns at certain locations that match what we would expect to see from a cell-site simulator, but that’s as much as we can say from an initial pilot study.”

At the very least it also provides advocates and journalists with something to work with. In attempting last year to discover whether Seattle police were using Stingrays, I found myself lacking in pointed questions to ask: although I received an unequivocal “no,” rather than a brush-off, it would have been nice to have something specific in mind, like a location or operation. I may just ask DHS about the suspicious signal mentioned above.

Unfortunately, the team wasn’t able to get their hands on an actual IMSI catcher to ground-truth these findings — the devices are jealously guarded by their keepers and information about them is really only available through leaked documents and the occasional missed redaction. Smith told me in an email that they did, however, roll their own Stingray-esque device based on what they know of how the things work.

Researchers Peter Ney (left) and Ian Smith

The detection kits contained around $500 worth of parts, all of which are specified in the paper describing the work. Smith suggested the cost could come down with scale, though.

“We’re eager to push this out into the community and find partners who can crowdsource more data collection and begin to connect the dots in meaningful ways,” he said.

Transparency advocates would love to have a working system like this, certainly, though it must also be said that the criminal element would find it useful too. But that’s the case with any tool, including IMSI catchers.

You can find out more about the tool or explore the data the team has collected at the SeaGlass site.

Featured Image: UW / SeaGlass