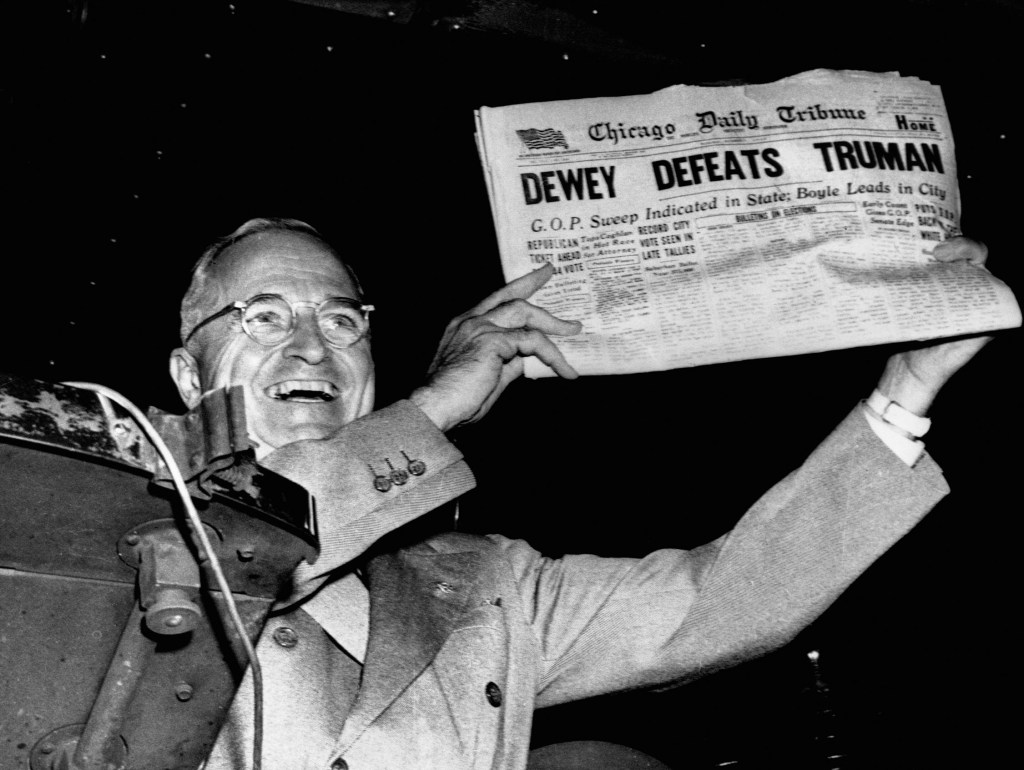

Everyone, even our new president, seems to be talking about “fake news” — just look at how Google searches have spiked over the past few months. But what does fake news actually mean?

On one level, the term seems pretty self-explanatory. Fake news is a story that’s completely false, usually invented for traffic and ad revenue, or to advance a political agenda — or both.

News hoaxes aren’t new, but there’s a growing sense that social media, particularly Facebook, has made it easier for these stories to spread, and for fake news to become a viable business model. (Who’s actually publishing these stories? Well, their exact identity is still a bit mysterious.)

For example, a study by BuzzSumo found that the biggest fake news story of 2016, about then-President Barack Obama supposedly banning the Pledge of Allegiance in schools, received more than 2 million Facebook shares, comments and reactions. Other popular stories — including one suggesting that Pope Francis had endorsed Donald Trump and another that Trump was offering free one-way tickets to Africa and Mexico — also got hundreds of thousands of shares, comments and reactions.

The impact of fake news

We’ve even seen arguments that Facebook contributed to the Electoral College victory of Donald Trump by facilitating the spread of fake news. In response, the social network has rolled out new features aimed at making it easier for users to flag and remove fake stories.

To be clear, economists Matthew Grentzkow of Stanford University and Hunt Allcott of New York University have done research showing that social media had a smaller influence on the election than you might think, with TV still playing a much larger role.

Still, fake news can have real consequences: As a result of the “Pizzagate” rumor supposedly tying Hillary Clinton to a child sex ring at the Washington, D.C. restaurant Comet Ping Pong, a man actually showed up at Comet Ping Pong with an assault rifle.

Can fake news be stopped? Or will it just keep spreading, until no one can tell the difference between the real stuff and the lies? One reason for optimism: As the issue has become more prominent, the big players — not just Facebook — have been talking about solutions.

Randall Rothenberg, president and CEO of the Interactive Advertising Bureau (a trade organization for online publishers and advertisers), has called for tech and media companies to “actively banish fakery, fraudulence, criminality, and hatred.” Some companies are already taking steps in this direction: Google said that it banned 200 publishers in the last quarter of of 2016 as part of an effort to crack down on fake news sites.

Enter President Trump

At the same time, the term itself has mutated — or, to put it more bluntly, co-opted, a trend that reached its peak with President Donald Trump describing both The New York Times and CNN as “fake news.”

To be clear, no one — not The Times, not CNN, not any publication — is above criticism, but that’s not exactly what Trump is doing. He’s taking the “fake news” label, originally used to describe fly-by-night websites that intentionally deceive readers, and slapping it on organizations with long histories of real journalism.

With his cries of “fake news” (and, conversely, Kellyanne Conway’s defense of “alternative facts”), Trump and his subordinates are giving Americans a simple message, one that he’s repeated plenty of times: “Believe me” — not the media.

In this environment, “fake news” is becoming the equivalent of “clickbait” — just another way of saying “news that I don’t like.” In fact, The Washington Post’s Margaret Sullivan has suggested that the term has become so “tainted” by misuse that it should be retired altogether: “Instead, call a lie a lie. Call a hoax a hoax. Call a conspiracy theory by its rightful name.”

The Times (where Sullivan used to serve as public editor) seems to be taking that advice, and perhaps others will follow suit. Will this help?Maybe it will just lead to more fragmentation, more reading of the news through an exclusively partisan lens. But even if that happens, it won’t make a lie anything other than a lie.

Everyone’s a fact checker

And for readers of the news, left wondering what to believe, this whole discussion has hopefully illustrated a simple, evergreen truth: That the news is created by people. Some of those people are honest and trustworthy, some of them are not and all of us are fallible (as TechCrunch readers surely know by now). And yes, liberals are susceptible, too.

So the news should always be read with some degree of skepticism — not a knee-jerk rejection of all media, but with a critical mind that’s aware of possible mistakes, biases and lies that also remains open to facts and theories that might make us uncomfortable.

Featured Image: Bryce Durbin/TechCrunch